In a Nutshell

In a Nutshell

A place set aside to answer 201 autobiographical questions

from a mother for her daughter. This may take awhile...join us if you like.27. This person significantly influenced my life growing up.My Great-Aunt Julia, called Auntie by all of her brother's descendants, was a major influence in my life. Auntie was born in July, 1900 and was a very forward thinking young woman. Her parents had refused to have the vow of obedience in their wedding ceremony, and the example they set marked both of their children. Because men were supposed to be in charge, my grandfather took a lot of heat about his "unwomanly" mother, which I have always felt influenced his choice of my grandmother as a wife -- she was willing to let him deal with the world while she dealt with the home and took his word as law. She even signed all of the letters she wrote to family and mutual friends "Percy and Lillian" because the man's name should come first.

Auntie was affected in the opposite direction. She observed that her mother was better treated than the mothers of other children, that her father listened to and respected his wife. She liked what she saw and emulated it. Auntie was very independent. When she graduated from high school, in 1918, she went to work for a doctor, assisting in the delivery of babies. At that time, well bred young ladies didn't do anything so forward and bold. The proper woman for that job was middle-aged and, if possible, married. I've told you about when

my Great-grandfather bought a car that he was unable to learn to drive and turned it over to her. Auntie, from all I've been told was a pretty fearless young woman. She was married twice, divorced both times. She owned two businesses of her own during her lifetime.

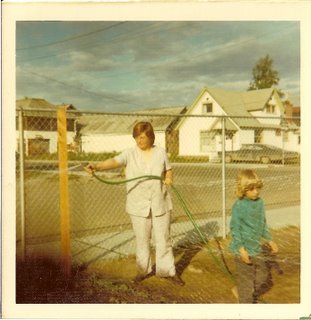

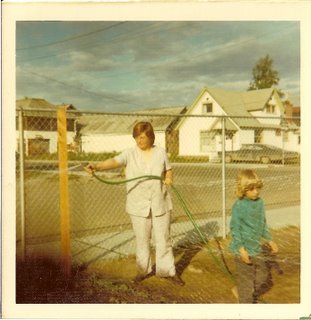

She was always a force in my life. She went to stay with my parents when I was born and helped to deliver me. It was she who later told me that my father kissed me before I was even washed off and that when my mother was told I had weighed six pounds she said, "Six of them!" Just as though, said Auntie laughing, she'd had a litter.

Auntie loved to tell me about the time, when I was about four, she took me from Modesto to San Francisco on the Greyhound bus to buy a coat. I was chattering up a storm, when I suddenly asked, "Auntie, do you know how to keep from having babies?" and she immediately knew that I had heard my father tell a joke and the answer wasn't anything I understood or that she wanted the other passengers to hear me say. Also, that attention hog that I was, there was no way she could get me to whisper it to her. She put me off and put me off and I kept asking and asking and finally she gave in and asked, "Well, Joy, how do you keep from having babies?" And I answered, "Lots of sulfa-denial and no acetol." (This joke was funnier in the 40s when sulfa drugs and acetol were in regular use in medical situations.) I got my desired laughter from the entire bus. And, as people were getting off at their various destinations, they all stopped on their way up the aisle, to say "Good-bye, Joy; good luck, Auntie."

Auntie sold her house and business in San Francisco when her mother died and returned to Modesto to take care of her father. She bought a house on a quiet, tree lined street, got a job at a local builders, and settled in. I remember visiting them many times over the years, and the house was always so exotic and glamorous to me. She had Ming vases and lovely pastoral paintings and incense. There were glass wind chimes in the back yard and cut flowers in the house. She cooked fascinating things I'd never heard of before, as well as the kind of staples a girl would learn growing up on a farm like chicken and dumplings and ox-tail soup.

Great-grandpa died not long before I was 16, and Daddy and I were at odds and fighting all the time. So, I went to live with her. Into that quiet, elegant house with the wisteria arbor and the cool rooms. To be the center of attention for a woman who had never had a child and now got her chance, as she told Mama, to attend parent-teacher meetings and the PTA. We went to movies and school plays and out to dinner in restaurants I'd never thought about before. She taught me to eat avocados and to keep a soup pot on the back burner in the winter, adding all of the water the vegetables had been cooked in and the left over vegies and meat to it. Mama couldn't stand eggs and Auntie remembered taking her to a brunch at a friends and Mama being unable to eat anything. Since I had learned to not like eggs from Mama, Auntie taught me, one step at a time, from scrambled eggs with cheese to soft boiled eggs, to eat and enjoy them.

Every Friday we had our hair done. We walked by a dress shop on our way and often the next week I would come home to see a dress that I had noticed in the window, but not mentioned and certainly not asked for, laying on my bed. Mama later told me that Auntie told her that when I would see something I liked my eyes would light up and she delighted in surprising me by buying it later.

For my 17th birthday we were invited out for three birthday dinners, and Auntie cooked one for me as well. Grandma asked me what I wanted, and I said, "fried chicken and angel food cake;" Mommy Lyle across the street asked me what I wanted, and I said, "fried chicken and angel food cake;" Mama asked me what I wanted, and I said, "fried chicken and angel food cake;" and Auntie asked me what I wanted, and I said, "fried chicken and angel food cake." At one point, Auntie asked me if I was sure I wouldn't like something else at one of those meals. "Oh, no. I love fried chicken and angel food cake," I answered obliviously. Only years later did I realize that while I

got to eat fried chicken and angel food cake four nights in a row, Auntie

had to. But, she never complained about it.

When I first went to live with Auntie, I had been well trained by Daddy that adults were Ma'am and Sir. She couldn't stand for me to say "Yes, ma'am" to her and worked hard to train me out of it. She had been very upset when I came home from boarding school at nine with as she told my mother, "all of her passion and delight crushed out of her;" she couldn't endure seeing it happen again.

She encouraged me to become whatever I wanted to be. She sent me to El Paso one summer to visit my friend Linda who I hadn't seen in years but was worried about because of something she had written to me. She had Kate come and spend time with us because I missed her. My friends were always welcome, and she never acted amused when we carried on the way inexperienced teens do and talked about some hair brained scheme to solve the problems of the world. My friends loved her -- she respected us, she fed us, she joined in our conversations when we wanted her and left us alone when we didn't. All of my friends had home situations that were more than a touch dysfunctional. I was the only one who lived in a home that was not.

I was never in trouble when I lived with Auntie. She had reasonable standards and was pleased with me. She was fun to talk to and could guide me to books and music that I might not otherwise find. She was able to talk about ideas.

And once in a while her friend Jack would come to visit from out of town, and they would go out, leaving me across town with my grandparents for the night. I didn't realize right away that they were lovers and had been for a long time. Jack was Catholic and married to a woman in an institution.

I wanted to be like her. Independent and kind and smart and with a personal style all of my own. One day, in the beauty parlor, I heard another customer say, "Julia's niece is growing up just like her -- as eccentric as they come." I was so pleased. When I repeated it to her, she wasn't.

Auntie died my freshman year of college. She left two trust funds. One was for me, to send me to college -- she made a deal with my grandfather that if it wasn't enough, he would take care of what was needed, and if it was more than enough, he would get the remainder. When I quit school in my sophomore year, that trust was closed. (My Aunt Flo later helped me complete college.) The other trust was for Auntie's other five great nieces and nephews. It sent them all to college, and when Colleen finally admitted she wasn't going to graduate, the remainder was split five ways.

And the other things she left were: a hole in my life where she should be, the self-confidence I had developed in her house. a love of the smell of wisteria and the sound of mocking birds singing in the moonlight, a re-affirmation that, just as my father had modeled for me, there was a way to relate to children that never involved sarcasm or name calling or reciting all of the wrongs the child has committed in her life.

Such as the time, in the early days of flight, a pilot flew the first plane into Barrow one cold, windy, winter day. He landed his little two-seater plane, and then was in a real fix, as there was nothing to tie it down to. No fence posts.

Such as the time, in the early days of flight, a pilot flew the first plane into Barrow one cold, windy, winter day. He landed his little two-seater plane, and then was in a real fix, as there was nothing to tie it down to. No fence posts.  No trees. While he was trying to figure out what to do, and holding on to the plane with all of his might, fighting the wind that was trying to snatch it from his hands and his life, the local men poured out of their homes, tied ropes to various parts of the plane, pulled the ropes out in straight lines, laid them on the ground and peed on them. The hot urine immediately froze solid to the ice under it and the plane was safely anchored for his entire stop over.

No trees. While he was trying to figure out what to do, and holding on to the plane with all of his might, fighting the wind that was trying to snatch it from his hands and his life, the local men poured out of their homes, tied ropes to various parts of the plane, pulled the ropes out in straight lines, laid them on the ground and peed on them. The hot urine immediately froze solid to the ice under it and the plane was safely anchored for his entire stop over.